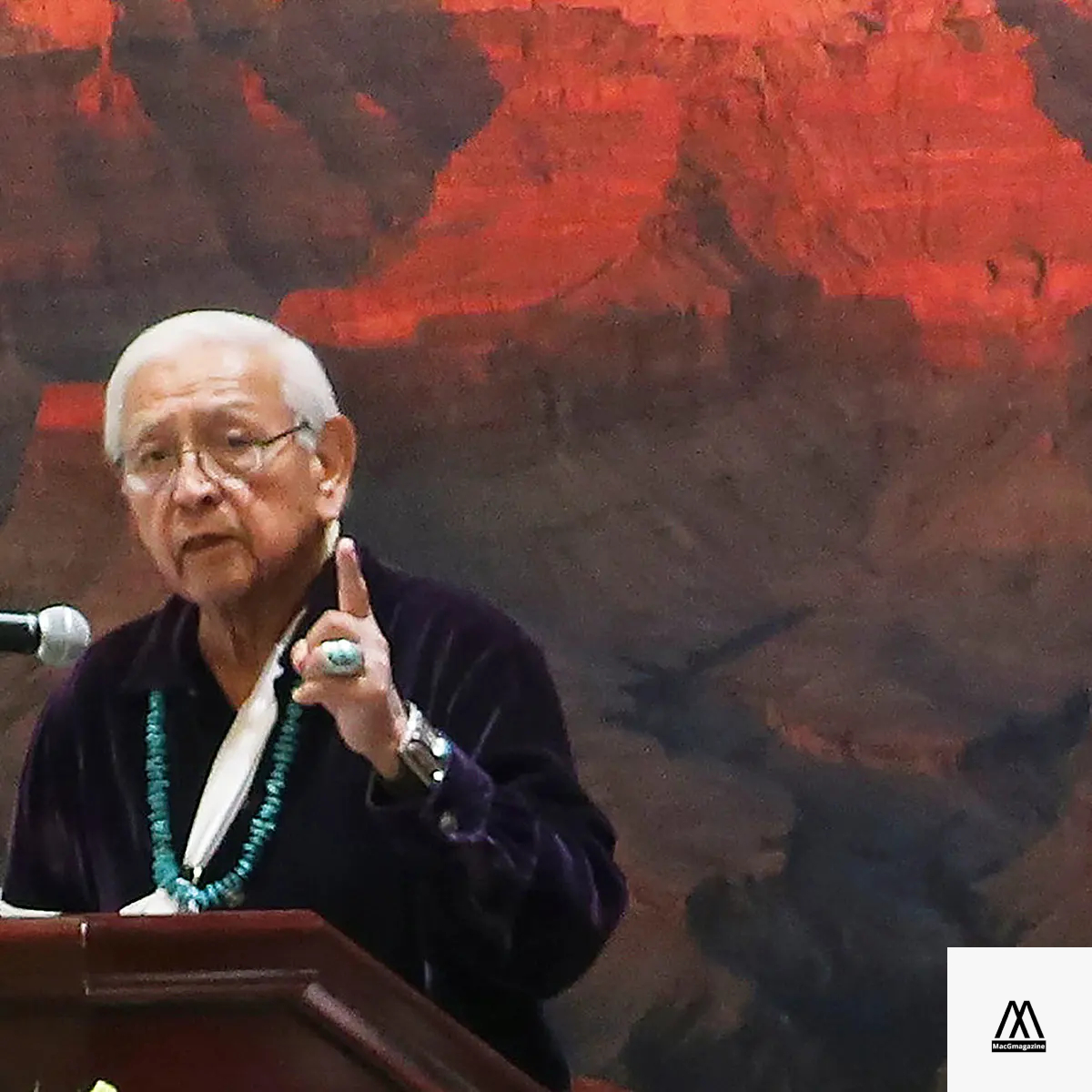

Peterson Zach, the monumental leader of the Navajo Nation who led the tribe through an era of political turmoil and worked tirelessly to right wrongs against Native Americans, has died.

Peterson Zah dies

In 1990, Zaher was the first president elected by the Navajo Nation, the largest tribal reservation in the United States, after the government was reorganized into three branches to prevent the concentration of power in the presidency. At the time, the tribe was reeling from deadly riots sparked a year earlier by Zaher’s political opponent, former chairman Peter McDonald.

Zach promised to rebuild the tribe, support families and education, and speak to people with respect, said longtime friend Eric Eberhardt. In Washington, Zach said he would drive his old pickup around the reservation, sit on the ground and listen to people fight, and he felt comfortable wearing a suit to represent the Navajo.

Source: Fronteras Desk

How Did Peterson Zah Die?

“People trust him, they know he’s honest,” Eberhardt said Tuesday. Zaha will be buried in a private funeral on Saturday morning. A local reception will follow outside of Window Rock, Arizona. His family is grateful for the love and support they have received.

“It was heartwarming for the family to hear so many people share their stories about Peterson,” the statement released Wednesday night said. Aspiring politicians in the Navajo Nation and beyond seek Zach’s advice and support. He joined Hillary Clinton in a march on the Navajo Nation a month before Bill Clinton was elected president. Zah later campaigned for Hillary Clinton’s presidential bid.

Over the years, he has recorded numerous campaign ads in the Navajo language that have been played on the radio, most of them on the Democratic side. But he also befriended Republicans, including the late U.S. Sen. John McCain of Arizona, who supported McCain in the 2000 presidential election and believed he could work across the aisle. Zach was born in December 1937 on remote Low Mountain, part of a reservation embroiled in a decades-long land dispute with the neighboring Hopi tribe that has displaced several thousand Navajo and hundreds of Hopi.

Eberhardt said he attended boarding school and graduated from the Phoenix Indian School, dismissing the idea that he wasn’t ready for college. Zach attended community college and then received a basketball scholarship to Arizona State University where he received his education. In the reserve, he continues to teach carpentry and other professional skills. He later co-founded a federally funded legal advocacy organization serving the Navajo, Hopi and Apache nations that still exists today.

Although Zach never held significant elected office, he won the tribal chairmanship in 1982, Eberhardt said, driving his 1950s International pickup truck. Repaired and driven by himself for decades, it has become a hallmark of his understated style. . Under Zaha, the tribe created a permanent foundation in 1985, now worth billions of dollars, after winning a court battle with Kerr McGee, who found the tribe owed taxes to mining companies. All coal, pipeline, oil and gas leases were renegotiated with increased payments to tribes. A portion of this money is added to the permanent fund each year.

Former Hopi President Ivan Sidney, whose tenure overlaps with Zaha’s, said the pair eased tensions between neighboring tribes over land disputes. They agreed to meet in person without lawyers to figure out how to help their people. Even after the deadline, they attended tribal initiations and other events together. Zach would say, ‘Let’s think about it,'” Sydney recalled Wednesday after visiting Zach’s family. “We will walk together, sit together, present together.”

Zaha is sometimes called the Native American Robert Kennedy because of his charisma, ideas and ability to get things done, including lobbying federal officials to ensure Native Americans can keep cacti as religious sacraments, his longtime friend Charles Wilkinson said last year. Zah has also worked to ensure that Native Americans are represented in federal environmental laws such as the Clean Water Act and the Clean Air Act.

Read Also: Marcel Amont, Passed Away At The Age Of 93